Helping Out with Some Malaria Research' - A Postcard from Uganda

(Published: January, 2022, Volume 22, Number 1, Issue #53) (Table Of Contents)(Author: David Frye)

Occasionally, items that pass through the mail show ties to global efforts to combat malaria - a widespread disease passed by various species of mosquito - by bearing postage stamps that highlight those efforts. The second class of ties includes postmarks with slogans that draw attention to antimalarial programs. Finally, the third class of connections looks for antimalarial endeavors in the contents of the messages that make their ways through the world's postal systems.

This postcard profile highlights a message that refers to volunteer work with malaria research, which a writer penned on a postcard mailed from Uganda to San Antonio, Texas, in March 2006. The message provided enough personal details to make an informed online search that located the writer. She agreed to fill in the background of the antimalarial work mentioned in the postcard's message.

Postcard

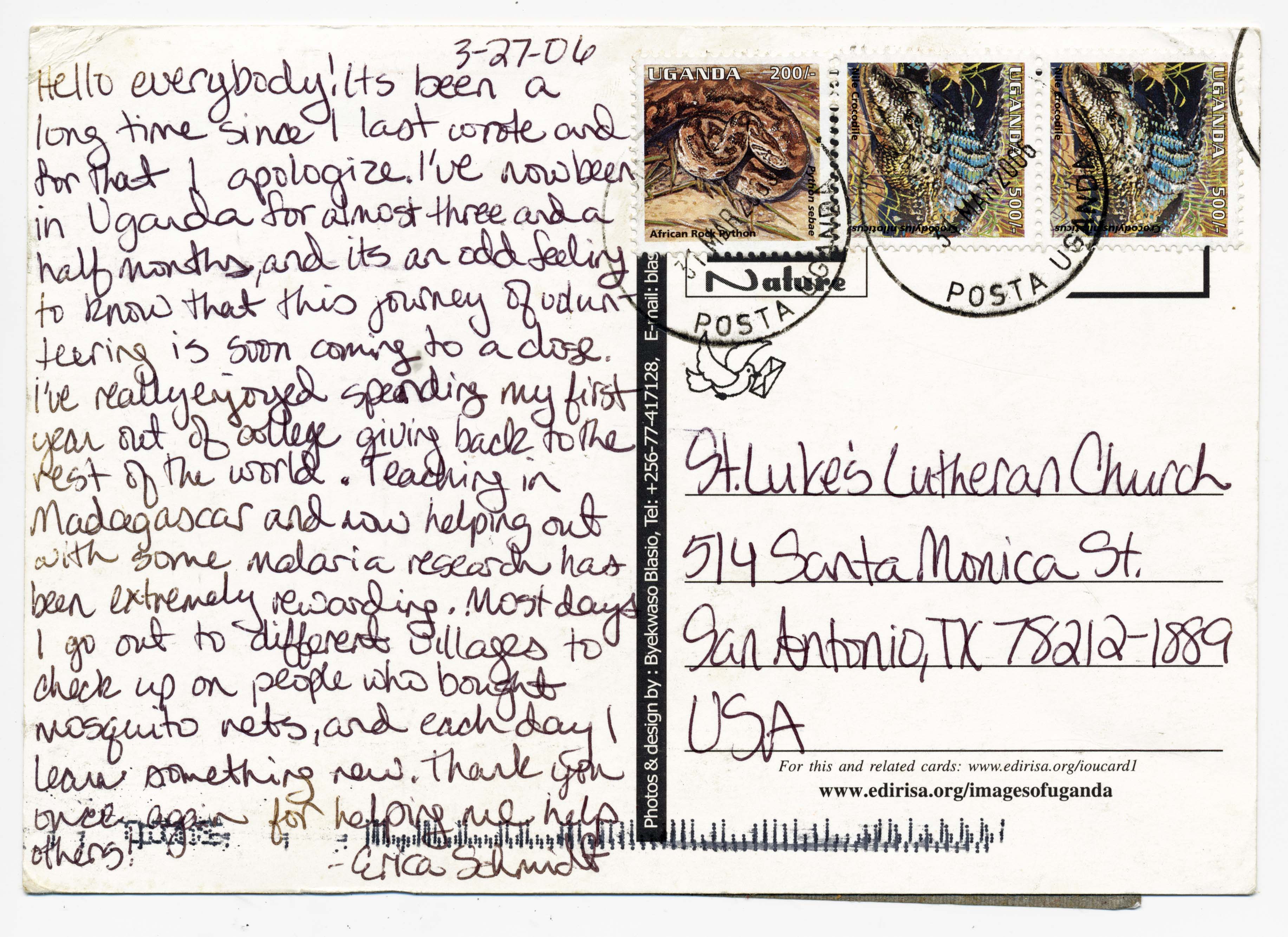

Figure 1 shows the message side of a picture postcard franked with three stamps from Uganda's Reptile definitive series with values in Ugandan shillings (UGX). One 200/- UGX stamp depicts an African Rock Python, and a vertical pair of the 500/- UGX issue illustrates the Nile Crocodile. Together, they paid the prevailing 1,200/- UGX rate for postcards mailed to North America (Posta Uganda, 2007). The message includes a 27 March 2006 writing date while the postmark indicates the postcard passed through the hands of a postal clerk on 31 March 2006. The circular date stamps include the phrase "Posta Uganda" but do not indicate the town of mailing. When the postcard reached the United States, the U.S. Postal Service's processing equipment added the POSTNET barcode across the bottom of the postcard as an aid to automated sorting before carrier delivery.

MessageErica Schmidt, the postcard's sender, wrote a message to the people of St. Luke's Lutheran Church in San Antonio. Online searches reveal that this congregation disbanded sometime between the postcard's mailing and 2020. She wrote:

3-27-06

Hello everybody! It's been a long time since I last wrote and for that I apologize. I've now been in Uganda for almost three and a half months, and it's an odd feeling to know that this journey of volunteering is soon coming to a close. I've really enjoyed spending my first year out of college giving back to the rest of the world. Teaching in Madagascar and now helping out with some malaria research has been extremely rewarding. Most days I go out to different villages to check up on people who bought mosquito nets, and each day I learn something new. Thank you once again for helping me help others!

-Erica Schmidt

In the second half of the message, she mentions working with malaria research and visiting villages to see how people were working with mosquito nets they had purchased. These two sentences provide the references that make this postcard worthy of study from the perspective of the postal history of global antimalarial programs.

InterviewErica Schmidt's message presented enough details about her life to enable an online search to find her current contact information. In a reply to a message asking for research assistance, Erica Schmidt-Portnoy wrote, "This is definitely a postcard I wrote during my time in Uganda in 2006! I'm so curious how you landed upon it, and I'm happy to answer any questions you have." She responded by email to several questions. Here is the conversation.

Question: You wrote that you had served as a volunteer for almost three and one-half months before you sent this postcard. What led you to volunteer to work in Uganda? What program were you working with? How were you "helping out with some malaria research"?

Response: I studied abroad in Uganda my junior year of college and had such a positive experience that I wanted to go back after I graduated. I actually volunteered for 3.5 months in Madagascar in the fall of 2005 before moving on to Uganda during the spring of 2006. In Uganda, I volunteered with Soft Power Education (http://www.softpowereducation.com/), where I spent most of my time going into villages around Jinja with a Ugandan doctor. We would host malaria workshops that pulled in around 50 people at times-those workshops would equip community members with education around malaria, including the impact sleeping with mosquito nets has on reducing the chances of contracting and time lost at work because you have to stay home sick. Following the workshops, we would sell mosquito nets at a significantly reduced price, because Soft Power Education would offset most of the cost. Charging even a small amount was usually helpful because it increased buy-in and ownership. We would then go back to the same village a few weeks later to follow up with people who had purchased a net to see how they were using the net, make sure it was being used effectively (wrapping the bottom under your bed instead of leaving it open for mosquitoes to fly into), and gauge whether people had gotten malaria since sleeping with a net.

Question: Where in Uganda did you visit "the different villages to check up on people who bought mosquito nets"? What did you do as part of those visits? Do you have any particularly vivid memories that you'd like to share?

Response: I think I answered part of this above. It's very humbling to be invited into someone's home, nearly always a mud hut with not much more than a bed and a few cooking tools, to check how their mosquito net is working for them. It was always kindness and a genuine interest in connecting with one another that made conversations about a serious topic meaningful and lasting.

Question: What differences did you see the distribution of mosquito nets making in the lives of the people of Uganda?

Response: We'd collect data on the rates of people getting malaria when sleeping with a net correctly and those who continued to sleep without, and while I don't have it anymore, I remember anecdotally that we saw far lower rates of malaria when people used nets correctly. For people in rural Uganda, I believe nets have a tremendous impact, and this is because contracting malaria has an equally tremendous impact. When people contract a severe case of malaria, it can take them out of work for days, and they may or may not be able to access medication to even reduce some of the symptoms. In a context where people usually only get paid if they show up for work, losing out on that income for your family can be devastating and continue to keep you in the harsh economic situation you are in. Malaria highlights so many of the disparities that exist in our world, with the world's poorest, those often living in rural villages, suffering from malaria far more often than those with more wealth and access to resources.

Question: How did your experience change your outlook on the global effort to combat malaria?

Response: My experience volunteering in malaria education made me a lifelong supporter of the global effort to combat malaria. While not an issue we have to face in the US, it has a significant impact on the economies of many developing countries and livelihoods of millions of families around the world. Additional dollars need to be dedicated to combating malaria so the world can get to the point where it can start talking about eradicating it.

Question: Do you have any other reflections you'd like to share?

Response: I think it's extraordinarily important for Americans to experience life outside the States. We continue to be a very privileged society, and while inequalities exist within our own country, it is eye-opening to witness how grateful and content people are without having nearly the wealth that Americans perceive to be needed in order to live a happy life.

Context

Erica said that she volunteered with Soft Power Education when she spent her months in Uganda in 2006. Her LinkedIn profile notes that served as a malaria educator from January through April 2006. During that time, she "implemented community education trainings on malaria: its causes, treatment, and preventative measures" ... and "[c]onducted visits and interviews in rural Ugandan homes to collect data on utilization of mosquito nets and their effectiveness in reducing rates of malaria" (Erica Schmidt-Portnoy, LinkedIn.com, 2020).

The World Health Organization issued its World Malaria Report 2008, which provides a compact summary of the situation in Uganda in 2006, the year that Erica volunteered there. The report states:

Uganda had an estimated 10.6 million malaria cases in 2006. Transmission occurs all year round in most parts of the country. Case reports were presented only in round numbers from 2001 to 2005, and do not provide a basis for evaluating incidence trends although programme reports show a fall in cases and deaths between 2005 and 2006. IRS [indoor residual spraying] began on a limited scale in 2006, protecting 500 000 people at risk. 1.9 million LLIN [long-lasting insecticidal nets] were distributed in 2005 and 2006. A 2006 survey showed that 34% of households owned a mosquito net, but only 10% of children slept under an ITN [insecticide-treated net]. Although 15 million ACT [artemisinin-based combination therapy] courses were reportedly delivered in 2006, survey data indicate that only 3% of febrile children received ACT. Funding for malaria control exceeded US$ 75 million in 2006, supported by government, the Global Fund, UN [United Nations] agencies and other external donors (World Health Organization, 2008, p. 120).

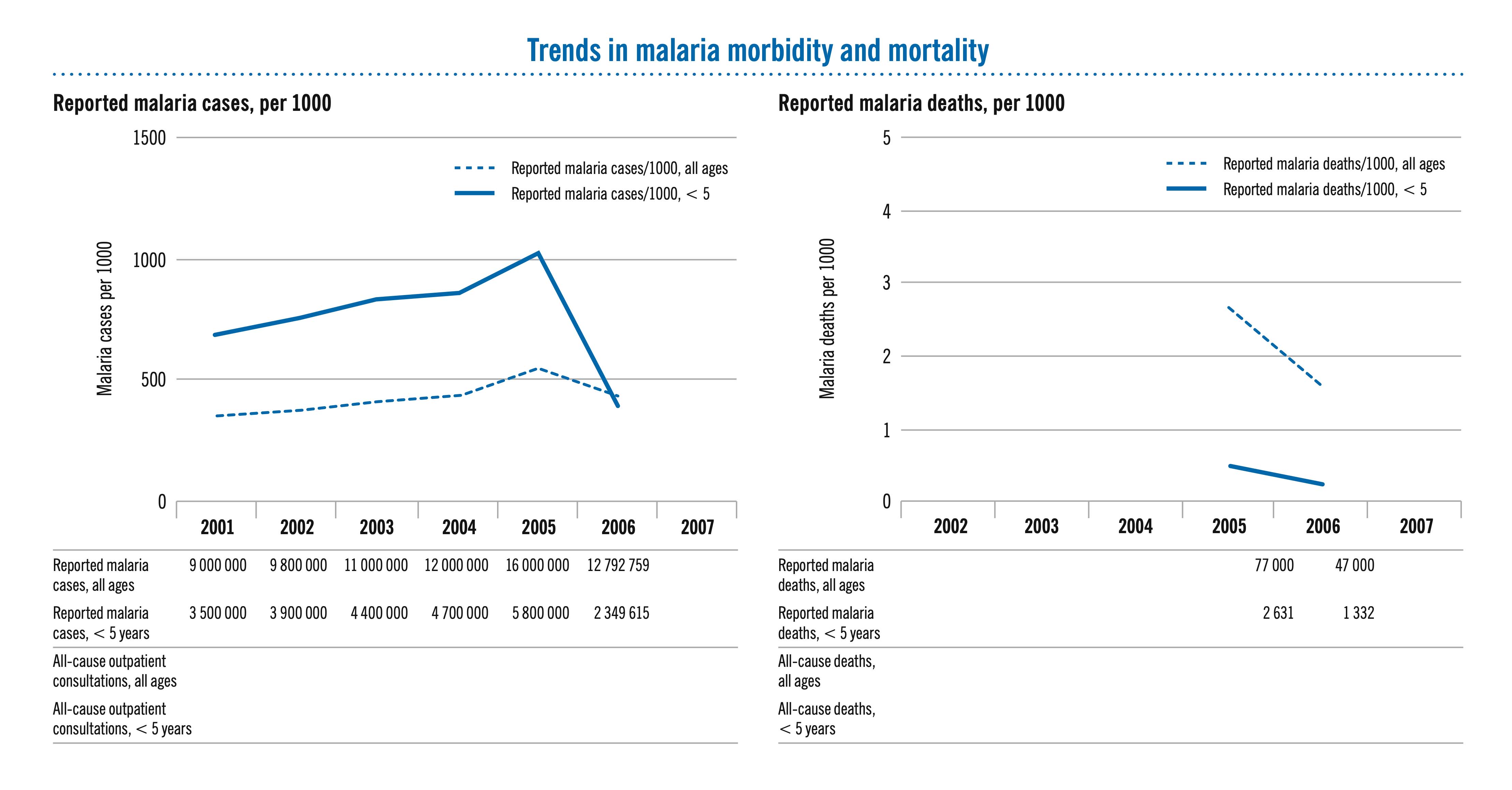

The report shows the effects of these measures on the number of people who became ill with malaria and who died from the disease. In particular, the incidence of reported cases of malaria among children under the age of five decreased from an estimated 5,800,000 in 2005 to only 2,349,615 in 2006, as shown in the charts in Fig. 4, below. In addition, the number of children under the age of five who died from malaria was nearly halved, falling from 2,631 in 2005 to 1,332 in 2006. The declines show the effects of efforts-including Erica's volunteer work-to distribute and ensure the use of mosquito nets in Uganda.

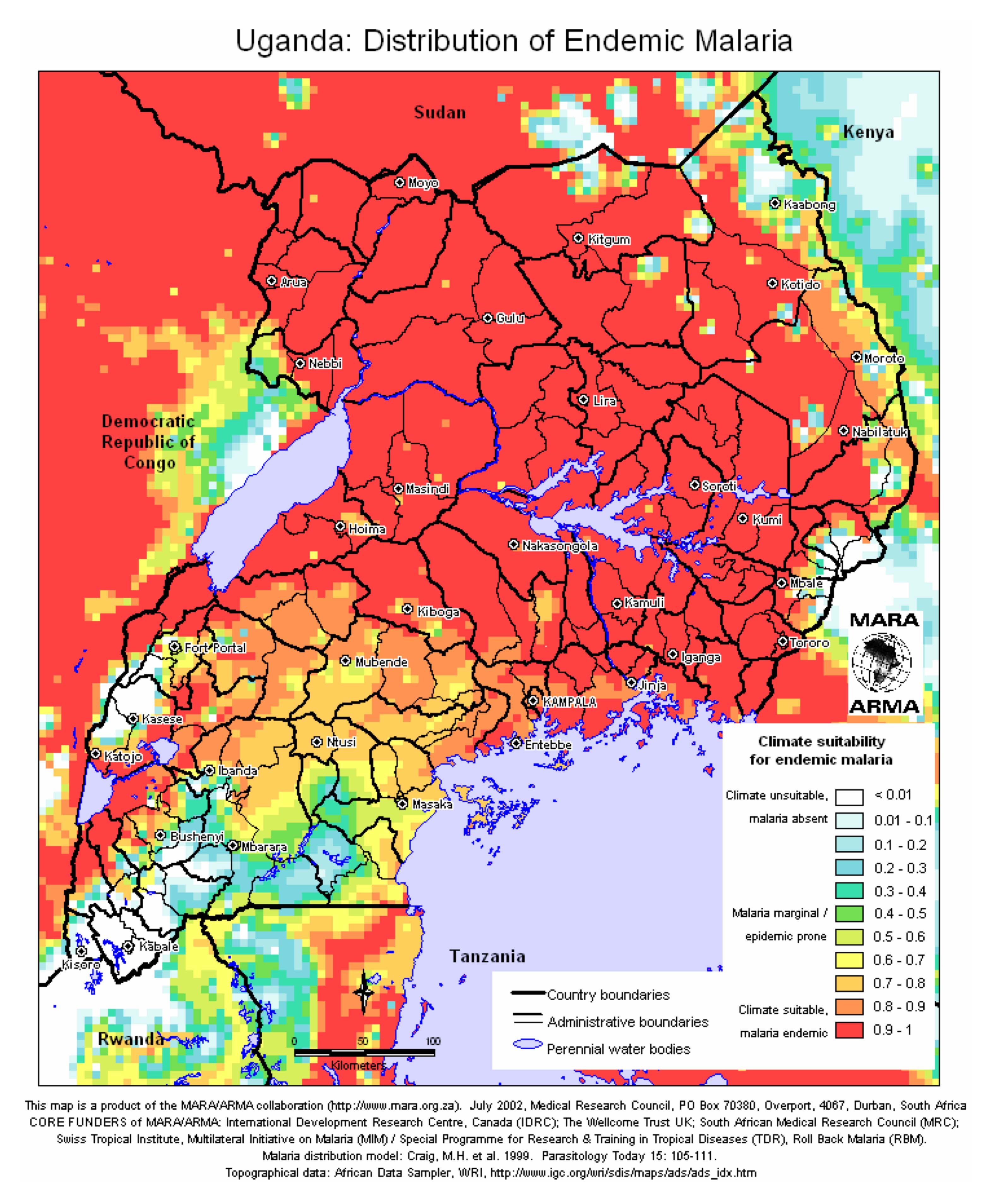

Erica wrote that she worked with people living in the villages around Jinja. The map below in Fig. 5 shows the location of Jinja, on the northern shore of Lake Victoria east of Kampala, Uganda's capital. The map also depicts the prevalence of malaria. Jinja falls in the region in which malaria was endemic in 2002, the year depicted by the map's data.

In its "Malaria Control Action Plan FY 2006," the U.S. President's Malaria Initiative Uganda outlines a role for the nets that Erica worked to distribute, stating that various strategic plans

recognize that ITNs [insecticide-treated nets] are a key malaria control intervention[] and outline a rapid scale-up of ITN use nationwide. The main focus of the strategy is to create a demand for ITNs, ensure the availability of affordable nets, provide subsidized or free ITNs to vulnerable groups such as pregnant women, children under five and people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) and promote correct use of ITNs (p. 20). Efforts to combat malaria have continued in the years since Erica's time in Uganda. As one recent study notes, Uganda, ranked third in the total number of malaria cases in sub-Saharan Africa, experiences weather conditions that often allow transmission to occur all year round with only a few areas that experience low or unstable transmission [2]. Climate affects both the parasite and the mosquito. Mosquitoes are unable to survive in low humidity and their breeding grounds are expanded by rainfall. Plasmodium parasites are affected by temperature where their development slows as the temperature drops and stops at high temperatures, which is the reason why parasites can be found in temperate areas [3]. Malaria is the leading cause of morbidity in Uganda with 90-95 % of the population at risk and it contributing to approximately 13 % of under-five mortality. [4]. Children under the age of 5 years are among the most vulnerable to malaria infection as they have not yet developed any immunity to the disease [5] (Roberts and Matthews).

Erica's efforts contributed directly to the long-term project of reducing the impact on the people of Uganda, particularly its most vulnerable-children. The children whom Erica touched with her volunteer work in 2006 left a lasting impression on her. She described her experience with them in a testimonial recorded by Soft Power Education. She wrote:

What else I've missed the most since I've been home are the friends I quickly grew to love. Young and old presented themselves to me with more kindheartedness than I could have ever reciprocated, and the relationships I left with were consequently deep and long lasting. I loved walking down the road each morning to be greeted by every person I passed. My walks back home also never went empty-handed as children ran faster than Olympic sprinters to grab my hand before the others did; by the time I arrived home I sometimes had as many as ten children by my side. Ten children whose poverty is great but whose happiness and love for others are far greater. I feel fortunate I was able to see that (SoftPowerEducation.com, 2020).

Conclusion

Only a few lines on the message side of a fourteen-year-old postcard serve to tie this bit of ephemera to the larger world and one of its perennial battles against a disease that continues to kill hundreds of thousands of people each year. When Erica wrote that "helping out with some malaria research has been extremely rewarding. Most days I go out to different villages to check up on people who bought mosquito nets, and each day I learn something new," she could not have known the journey her message would take. Not only would the postcard make its way from Uganda to San Antonio in 2006, but it somehow would end up for sale online for $1.50 in 2020 and catch the eye of a postal historian who not only looks at the stamps and markings on postcards but reads the messages they carry across the years.

References- Posta Uganda, "Mail Services", retrieved from Internet Archive, accessed 14 June 2020.

- Danielle Roberts and Glenda Matthews, "Risk factors of malaria in children under the age of five years old in Uganda"", Malaria Journal, 2016, 15:246, ; accessed 13 June 2020.

- Erica Schmidt, "Volunteer December 2005 to April 2006", accessed 13 June 2020.

- Erica Schmidt-Portnoy, email correspondence with the author, 13-XX June 2020.

- Erica Schmidt-Portnoy, "LinkedIn Profile, accessed 21 June 2020.

- U.S. President's Malaria Initiative, "Uganda: Malaria Country Action Plan FY 2006" February 2006, accessed 9 June 2020.

- World Health Organization, World Malaria Report 2008, "Uganda", pp. 120-122, accessed 9 June 2020.

- Jerry P. Lanier, "Malaria is the leading cause of illness and death in Uganda", accessed 13 June 2020.

- Julius Julian Lutwama, "Type Localities of Mosquito Species in Uganda", International Journal of Tropical Insect Science, Vol. 20, No. 1, 2000, pp. 51-60, accessed 13 June 2020.

- Ministry of Health, Republic of Uganda, "National Malaria Control Program", accessed 13 June 2020.

Acknowledgment

This paper depends upon the gracious response of Erica Schmidt-Portnoy to an out-of-the-blue request to share her recollections and photographs of her time in Uganda.

About the Author

David M. Frye collects items to inform his study of modern United States postal history and southern and eastern Africa's post-colonial postal history. His writings have appeared in The Airpost Journal, Auxiliary Markings, B.E.A.-The Bulletin of the East Africa Study Circle, Forerunners, The Journal of the Rhodesian Study Circle, The Miasma Philatelist, Postal History Journal, The Postal Label Bulletin, The Stamp Forum Newsletter, The United States Specialist, Vatican Notes, and The Vermont Philatelist. A past member of the Board of Directors of the Postal History Society, he lives in Franklin, Massachusetts, and works in nearby Framingham as a clerk for the U.S. Postal Service.